Los caminantes: an odyssey across the Andes

The humming noise of trucks and cars on the highway that leads from Cúcuta to Bucaramanga, Colombia, muffles the cries of baby Jesús Rodríguez. His mother, Escaret González, carries him in her arms as she walks with her family to reach Peru.

She had thought about it before, but his birth is what prompted Escaret to leave her country. At first, she contemplated leaving him behind in Venezuela, but she changed her mind. "If I'm going to have a rough time, it'll be with him," she says. "I want to see him take his first steps, hear his first words."

Escaret, her husband and son will join her father-in-law in Peru. The others are going to Cali, which they think will take them about two weeks. Theirs is a desperate journey.

The first city they expect to reach is Bucaramanga, 187 km away. The trip would take four and a half hours by car. On foot on a narrow road, carrying luggage and kids, it'll take them several gruelling days. They will need to climb up to 3,442 meters and walk through moorland, where temperatures can be very low.

The group left Venezuela three months ago. They tried to stay in Cúcuta — where humanitarian organizations including the World Food Programme (WFP) are assisting migrants — but there were too many Venezuelans in the city and the situation was "rough," so they decided to move on.

Roxy Medina, Escaret's cousin and a young mother herself, cries when she says she left her 5-year-old son with his father. She also left behind her mother and brother, and a job as a security guard."We never thought of leaving Venezuela," she says. She doesn't want to go too far because she plans to go back for her son.

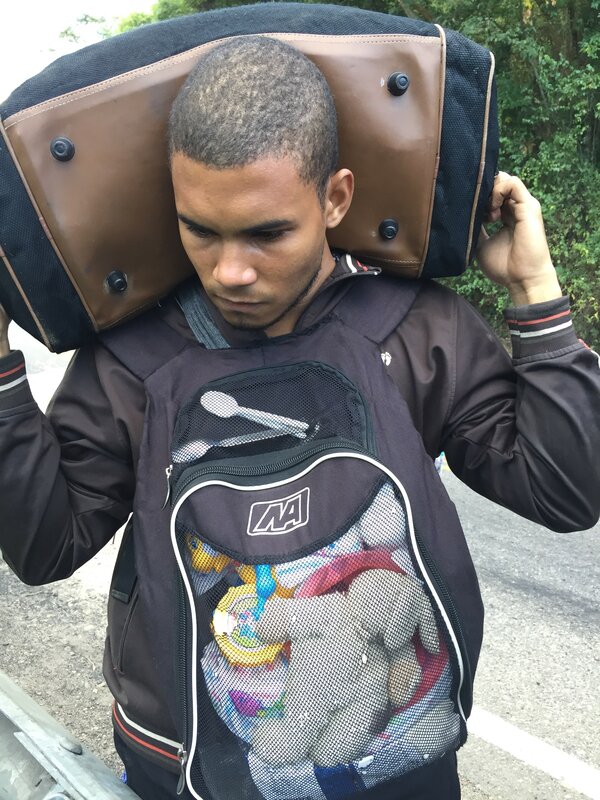

This family of caminantes — the name given to Venezuelans who are walking to Colombia and other countries in the region in search of a better future — carries clothes, blankets for the cold and jackets. Two of the women are walking in sandals. As is the case with most of the people who are walking across the mountains, they do not have money, water or food. Their cooler is empty. They survive thanks to the generosity of passers-by.

"They left me behind because I could not walk fast enough with my daughter in my arms."

Arliany Pérez is 20 and has a 2-year-old baby. She's taking a rest on the side of the road. Trucks drive past, barely two meters away from them. Although she's tired, she is not willing to give up. She knows what she is going through is for the well-being of her daughter.

Arliany comes from San Cristóbal, Venezuela. She crossed the border on foot and continued walking up the mountain. She hasn't reached the moorland at the top yet. She is not cold now but she's heard that she will have to wrap herself up very well. The news reported that a migrant woman died of hypothermia a few days ago.

She shares her story: "I've been walking for a day and a half. I left at 3 this morning with a group of people, but they left me behind because I can't walk that fast with my daughter in my arms."

Arliany is on her way to Bogotá. "I don't know anybody there," she says, "but I hope to find a job and give my daughter a better future, where she can have food and be safe from crime." She explains that she's had to walk because she couldn't get a bus ticket without a passport.

Although she has sneakers in her small piece of luggage, Arliany is wearing slippers. She has little to warm herself up. During her long walk, she rested at an improvised shelter run by good-hearted people who want to help in any way they can. But that is not enough for the hundreds of Venezuelan migrants who are entering Colombia.

"This situation is tough," she says. "We find ourselves in a different world from our own, but we must keep walking. It's the only thing left for us to do."

At the request of the Colombian Government, in April of this year, WFP launched a humanitarian operation to provide food assistance to the increasing numbers of migrants in the departments of Arauca, La Guajira and Norte de Santander, located on the Colombian-Venezuelan border. Operations have now expanded to Nariño, a department in southern Colombia, through which Venezuelan migrants are transiting on the way to Ecuador, Peru and Chile.