What a difference a year can make

"Good news does not come often to the Sahel." Lena Savelli, Senegal Country Director for the World Food Programme (WFP) knows this only too well.

Exactly one year ago, she was travelling to the arid north of the country to see for herself how insufficient rainfall and poor harvests were threatening to push communities into hunger. It was the beginning of the ‘lean season' — the period between two harvests when food stocks are depleted — and people were already feeling the pinch: there was just not enough food for everyone.

Fast forward one year, and Savelli can smile a relieved smile. For the first time in six years, not one single department in Senegal is projected to fall into crisis level during the lean season — not even the north-eastern ones, where recurring drought and a burgeoning population make it notoriously difficult to guarantee that everyone has access to enough nutritious food all year round.

"In Matam last year, wherever you looked, all you could see was sand," Savelli says, recalling her visit to one of the country's most food-insecure departments. "If you go back now, you can tell the difference at a glance: where the sand once prevailed there are green patches where families are planting cabbage, lettuce, turnips, eggplants, onions, tomatoes and potatoes — making for healthier diets and additional revenues."

So, how did this transformation happen?

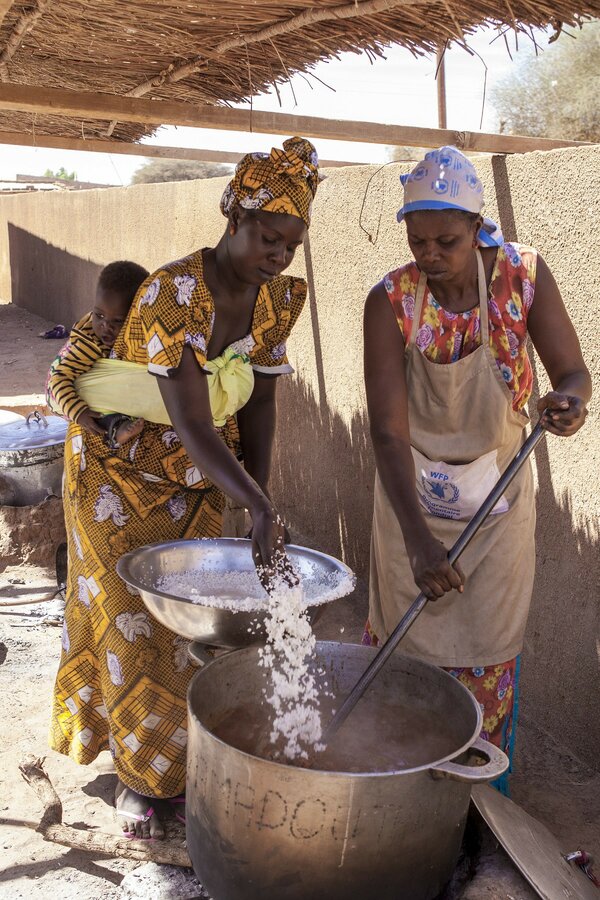

As soon as it became clear that crisis was looming, WFP stepped in to provide affected families with cash transfers so they could buy food to make it to the other side of the lean season. And it was not just about calories: those with special needs — pregnant and breastfeeding women, and children under 5 — would get additional specialized nutritious food.

"But we did not stop at helping people through the crisis," Savelli notes. "We stayed on afterwards and worked with local communities to make them more resilient ahead of the next drought," she adds, explaining that in the Sahel it is not a matter of ‘if' drought will come, but rather of ‘when'.

WFP and communities came together to identify concrete actions that would help them withstand the next climate-related shock. These included planting fodder for livestock to reduce the risk of potential conflict between pastoralists and arable farmers; fighting soil erosion by enhancing soil and water conservation and agroforestry; creating vegetable gardens both as a source for home consumption and as an income-generating activity; and introducing fuel-efficient stoves to reduce the impact on a fragile ecosystem and relieve families of the burden of collecting firewood.

As they implemented these actions, community members received support from WFP — not just in the form of food assistance but also through training, the provision of seeds and fertilizers, and a school feeding programme to keep children in class. The majority of those involved were women. "In this region, when food is scarce, women are the first to go without to the benefit of the children and men of the family. At age 12, one quarter of the girls has already dropped out of school and at 18 more than half of them are married," Savelli says. "We wanted to ensure our intervention had a positive impact on the lives of local women and girls."

The approach chosen has proven successful: the levels of food consumption among participating families have dramatically improved; 3,200 hectares of agricultural land have been rehabilitated for increased cereal, forage, fruit and vegetable production to the benefit of 8,500 families identified through the government social protection register; community dynamics have benefited from members joining efforts on common projects; and there has been a 7 percent increase in the number of children going to school.

"What we achieved in Matam through this integrated resilience-building approach shows that something that began as an emergency response to an impending crisis can be turned into the foundation of longer-term resilience and development. You do not want to find yourself in the same situation year in, year out," Savelli says.

"Thanks to the sustained engagement of the Senegalese government and the country's relative stability, we have been able to see results quicker," she adds.

Peace and stability create an enabling environment for focusing on food security. In parts of West Africa's Sahel region affected by insecurity and conflict, significant gains in the fight against hunger and malnutrition are under threat or being reversed.

"The rains have been better this year, but if we stay the course and consolidate our achievements, the next drought won't turn into a crisis. We want the good news to become the norm," she concludes.

The integrated resilience-building approach in Matam was made possible thanks to contributions from BMZ, USAID, France, Canada and Luxembourg. While the food security situation has improved in Senegal compared to 2018, some 340,000 people will still be facing food shortages during the lean season. WFP requires US$ 3.3 million to cover the needs of the most vulnerable people.